Tuesday, September 6, 2011

Ernst Mayr's Alpha, Beta, and Gamma levels of taxonomy did nothing to preserve the dignity of so-called descriptive taxonomy. Based on comments in the early pages of his 1942 Systematics and the Origin of Species, I suspect this was not an accident. Relegating revisionary work to the lowest rung on a progressively more scientific conceptual ladder with evolutionary considerations at the top was indeed his design. This made for a positive future for right-headed population-thinkers but left the observer thinking descriptive taxonomy was an anachronistic field for hermits in collections peering from under green eye shades and adjusting their armbands to reach that top pigeonhole.

It is time that we tease apart the diverse sub-fields of taxonomy and treat each with the dignity and importance befitting them. They each play coequally important scientific roles and are quite interdependent making it undesirable to treat them otherwise. What might a classification in place of Mayr's Greek letters be? Here is one stab at it.

1. Analytical Taxonomy: the sub-discipline of taxonomy concerned with formal descriptions of characters and species. Such descriptions are themselves based on rigorous, explicit, testable hypotheses about characters and a sophisticated set of theories and methods generally associated with character analysis and distinguishing informative characters from uninformative, polymorphic "traits". The corroborated hypotheses of analytical taxonomy are the factual foundations for phylogeny and phylogenetic classifications.

2. Phylogenetic Taxonomy/Systematics: the sub-discipline of taxonomy that is focused on cladistic analysis and phylogenetic classification.

3. Phyloinformatics and Nomenclature: the sub-discipline of taxonomy concerned with the efficient application of Linnaean nomenclature to provide unique identifiers for species in the form of binomials, a set of informative names for monophyletic higher taxa, and the management of taxonomic data, information, and knowledge in digital databases.

4. Translational Taxonomy: the sub-discipline of taxonomy that focuses on translating knowledge of characters, species, and clades into useful applied information for the benefit of science and society. The most familiar and simple example are accurate species identifications for field biologists. A rapidly emerging example is biomimicry where evolutionary adapations are co-opted by engineers, chemists, designers, and others to solve real-world problems.

You will immediately see, also, that these four branches of taxonomy are overlapping with permeable boundaries. This may benefit from a little tweaking but is, I submit, a step forward from Mayr's alpha/beta/gamma scheme.

Monday, August 29, 2011

Camoflaged Classification

“Camoflaging of courses to make them appear vocational is becoming an art of its own, and it is amusing to see colleges listing the only vocational benefit derivable from their courses of art as that of teaching art.

“If a course is limited to training teachers and those teachers are to teach others, just when will the vocational practice of the individual begin? How some schools do hate to roll up their sleeves and begin on the dishes!

“They will teach the lofty principles, only the theory, and George can flounder around and find the application later. And that is just why all the American Georges are about fifty years late in industrial art today.”

— Pedro J. Lemos, Leland Stanford Junior University, “The Industrial-Arts Magazine,” 1919.

The roll-up-your-sleeves, boots on the ground work of taxonomy is in a position not entirely dissimilar to that of the industrial arts at the turn of the last century. You can only talk about prosaic matters such as writing functional diagnostic keys or informative species descriptions, publishing floras or revisions or monographs, or translating cladograms (or, more often, neo-phenetic branching diagrams) into formal classifications and names, in hushed tones. Rather than openly celebrating the reciprocal illumination among fossils, anatomy, ontogeny, and molecular sequences, we as a community accede to the politically correct view that "phylogenies" are reconstructed from molecular data and that other characters are simply hung on this received knowledge of branching patterns like ornaments on a Christmas tree, after the fact and uncritically analyzed. We teach theory of phylogenetics and train students in the latest moelcular techiques, with no expectation that degree recipients will do much to address the messy, real world challenge of exploring, discovering, describing, classifying, and naming the ten million species of plants and animals that remain unknown to science. Refined, intelligent, right-minded people simply don't do taxonomy. They only teach the popular bits of it.

Sunday, August 21, 2011

All Species Are Not Created Equally

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

Playing Around with TaxaToy

Source:

http://taxatoy.ubio.org/

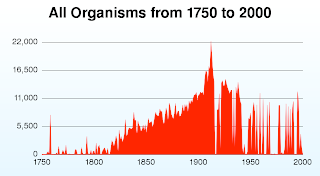

If you have not done so, I highly recommend you visit TaxaToy (link above), another clever contribution from the UBIO crew at Woods Hole. When you drill down to less inclusive taxa it is fascinating to see the pattern, frequently tracking the cyclic nature of monography and major revisions. Recognizing that all data is not yet available and particularly for recent years, the overall pattern is broadly consistent with seat of the pants history. There was a strong positive trend in the annual rate of species description with an expected hiatus at the time of the World Wars. Taxonomy bounced back quickly to pre-War levels but after WWII it never regained its positively accelerating trajectory. When one factors in the post-War growth in the academic workforce and the technological leaps since, this becomes a sad picture.

It is not coincidental that the WWII period was marked also by Huxley's "The New Systematics" and shortly thereafter Mayr's "Systematics and the Origin of Species" --- what might as well have been titled "Systematics the Demise of Taxonomy." Capitalizing on the wave of excitement (appropriately) associated with the rise of modern genetics and galvanizing a strong bias toward experimental biology already well established in the U.S. and Europe, Mayr and his comrades found it an easy matter to diminish "merely descriptive" taxonomy in the eyes of modern, right-minded, "population thinking" biologists.

If we are to learn enough about our planet's species to develop fact-based policies and strategies to achieve sustainable biodiversity, we not only must renew the upward course of species discovery and description, we must reverse the devastating effects of this short-sighted neglect of taxonomy.

Almost any combination of several options could immediately speed taxonomy by an order of magnitude to say 200,000 species per year: providing support to existing taxonomists in the form of staff and funding, modernizing the research platform for taxonomy with special investment in cyberinfrastructure, and focusing efforts of distributed collections and experts as demonstrated in the successful NSF-funded Planetary Biodiversity Inventory (PBI) projects.

Thursday, August 11, 2011

Evolution of Cybertaxonomy

Cybertaxonomy is entering an exciting new phase in its evolution. The early steps that have led to cybertaxonomy began with databasing in the 1980s. The focus now as then has largely been on digitizing existing taxonomic information and making it accessible via the Internet. Such digitial data access is extremely important, indeed essential, yet is merely the beginning. A negative consequence is that this emphasis on mobilizing existing information gives to some a false impression that taxonomic knowledge is static and, once created, simply needs to be moved around and made accessible through convenient portals. Taxonomy, of course, is a hypothesis-based science and unless hypotheses about characters, homologies, synapomorphies, species, and clades are continually tested by all and the latest evidence, then the value of that knowledge is diminished and it becomes less of a reflection of the natural world and mere historical artifacts.

Cybertaxonomy is entering an exciting new phase in its evolution. The early steps that have led to cybertaxonomy began with databasing in the 1980s. The focus now as then has largely been on digitizing existing taxonomic information and making it accessible via the Internet. Such digitial data access is extremely important, indeed essential, yet is merely the beginning. A negative consequence is that this emphasis on mobilizing existing information gives to some a false impression that taxonomic knowledge is static and, once created, simply needs to be moved around and made accessible through convenient portals. Taxonomy, of course, is a hypothesis-based science and unless hypotheses about characters, homologies, synapomorphies, species, and clades are continually tested by all and the latest evidence, then the value of that knowledge is diminished and it becomes less of a reflection of the natural world and mere historical artifacts.

We have entered the second phase in the evolution of cybertaxonomy that is characterized by a focus on meeting the needs of taxonomists to create new taxonomic knowledge and test and verify (or correct or replace) existing knowledge of characters, species, and clades. This will be a period of unprecedented discovery, when most of the 12 million living species of plants and animals are described and when a cyber-enabled research environment is built that will allow taxonomists to work more efficiently than ever before. The challenge will be to retain the best of the past 250 years of theory and practice while accelerating where possible --- without sacrifice of the quality and integrity of the research --- to make taxonomy as efficient and cost effective as possible. Assuming that we succeed in investing in taxonomy to increase discovery and description of species by an order of magnitude, the bulk of this major push for discovery can be completed by 2058--- the 300th anniversary of Systema naturae (10th ed.).

Cybertaxonomy would then move into a steady state of continual testing of characters, species, and clades and refining the ease and flexibility of accessing, synthesizing, aggregating, and using taxonomic information for many diverse purposes.

Taxonomy and Biodiversity Sustainability

If we are serious about biodiversity sustainability, and we had better be, then the common sense first step is to support taxonomy to create baseline knowledge of what species exist and where in the biosphere so that we have biological clarity about what it is we seek to see sustained and a fact based basis on which to measure our successes and failures.

Taxonomy remains out of fashion and we now have generations of environmental and even evolutionary biologists who are ignorant of the theories, traditions, history, and scientific rigor of modern taxonomy done well. This bias against taxonomy is as great a challenge and fully as important to the positive outcome of biodiversity sustainability efforts as the sum total of conservation projects around the world. No area of science offers as much return on investment as taxonomy and the field is ripe for investment now. Enabled by the latest advances in cyberinfrastructure, taxonomy is ready, able, and willing to launch the greatest period of species discovery ever seen and to arm society with the fundamental knowledge needed to achieve biodiversity sustainability.